Steve Morris recounts a two-week trip around Mongolia, the landlocked East Asian country sandwiched between northern China and Russia.

Words & photography: Steve Morris

It was autumn last year when I took a call from Peter Hanahoe, a fellow enthusiast and somebody I had travelled with over the past 20 years to photograph diesel locomotives in the USA and Baltic countries. “We are planning a trip to Mongolia next year,” he said. “It’s 100% diesel traction out there… fancy joining us?” It sounded like a real adventure to me, so I did not take long to respond positively… and what an adventure it turned out to be.

From the history of steam through to 21st century rail transport news, we have titles that cater for all rail enthusiasts. Covering diesels, modelling, steam and modern railways, check out our range of magazines and fantastic subscription offers.

There are only a handful of railway enthusiasts in Mongolia, one of whom is tour operator and guide Temuulen Batkhurel. Temuulen runs Monrailpic Tours, a company that specialises in railway-related photography, the only one in the country to do so. Along with his father Natsagdorj, a retired railway professional and fellow enthusiast, Temuulen has excellent contacts with the rail operator UBTZ, gaining access to facilities and track, plus direct contact with ‘control’. This allows for short-term planning, allowing visitors to be in the right place at the right time – something that is invaluable when you are in the middle of nowhere waiting for something to happen.

One of our group of six, Gary Thomas, already had contact with Temuulen having used his services before in 2022. His first trip had concentrated on the area around the capital Ulaanbaatar (UB) and locations north and south of the city. This time the scope was to increased to include the Gobi Desert to the south and the area around Darkhan in the north, the trip spread out over 18 days from start to finish.

Trying to undertake a trip like this without professional guidance is not really an option. Since 2023, entry to the country has been visa-free, but there are no direct flights to UB from Britain. We opted to go via Frankfurt with Mongolian operator MIAT, which flies four or five times a week, although a number of other routing options exist. With our itinerary finalised and flights booked, we were all set for a June 2024 departure.

Mongolia’s rail network

Mongolia is a vast country, landlocked by Russia to the north and China to the south. It covers more than 600,000 square miles – some six times larger than the UK – but with a population of less than 3.5 million, half of which live in the capital.

It is therefore not surprising that the vast majority of the country is open land, made up predominantly by grassland to the north and the Gobi Desert to the south. Apart from the area local to UB, and the trunk roads to the north and south, metalled roads are few and far between, and the dirt/sand tracks to outlying areas are in a very poor state. Our trip would not have been possible without off-road vehicles and Temuulen’s expert guidance.

The state of the roads also makes the railway an important, and in some cases the only realistic, mode of transport – with more than 90% of freight and 40% of passenger volumes moved this way.

The country was a relatively late entrant to rail transportation. The first section to be completed in November 1949 ran from the Russian border town of Naushki to Sukhbaatar and on to UB. It was then extended south to the Chinese border, this section opening in January 1956.

The combination of both sections now forms part of the Trans-Mongolian Railway that connects Ulan-Ude (on the Trans-Siberian Railway Russia) to Ulanqab (in Inner Mongolia, China), with 690 miles of the route within Mongolia. It is operated by the national operator UBTZ, a 51%/49% Mongolian/Russian joint-stock company.

Branch lines also exist to Tomortei (56 miles) in the far north to serve an iron ore mine, as well as coal mines at Sharyn Gol (39 miles) and Baganuur (53 miles), a copper mine at Erdenet (102 miles), fluorspar mine at Borondor (37 miles) and an oil refinery at Zuunbayan (39 miles).

More recently, ‘Part 1 New Railway Project’ opened in the Gobi Desert in 2022, with lines extending from the existing branch at Zuunbayan to Changi on the Chinese border, to the coal mines at Tawan Tolgoi, and to Gashuun Sukhait on the border. Finally, a 149 mile section not connected to the main line links Tschoibalsan in the north-east of the country to the Trans-Siberian at Borzya, having been used in the past to transport uranium.

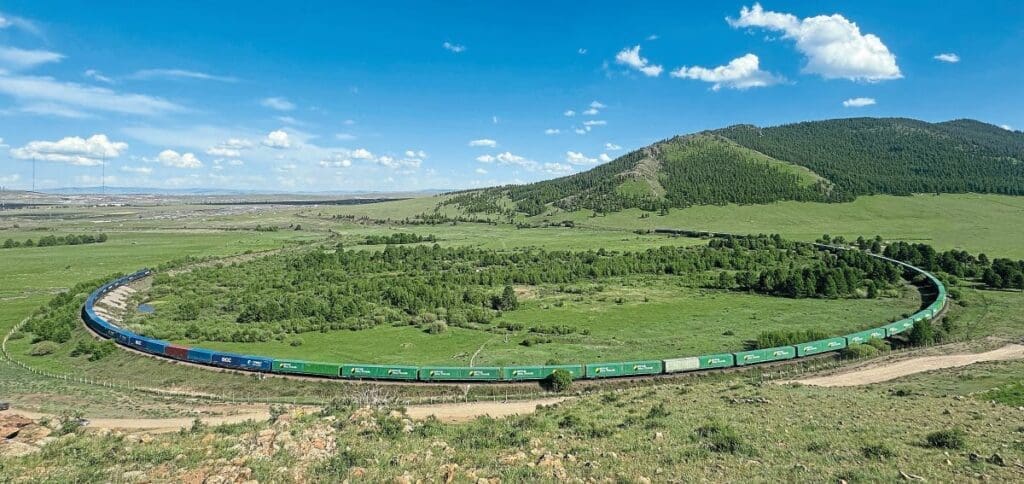

At the time of writing, the total length of the system comes to 1750 miles, almost entirely single line with passing loops. There are also no tunnels, which makes for a number of steeply-graded and curvaceous sections, while traction is 100% diesel.

Track is set at the standard Russian gauge of 1520mm, meaning a change of vehicle or bogies is required at Erenhot station (Inner Mongolia) to accommodate standard gauge 1435mm for trains travelling into China. Future expansion to the west of the country (the ‘Part 2 New Railway Project’) could see an additional 2900 miles added to the network, such is the pace of expansion. The future for Mongolian Railways certainly looks bright.

Freight and passenger traffic

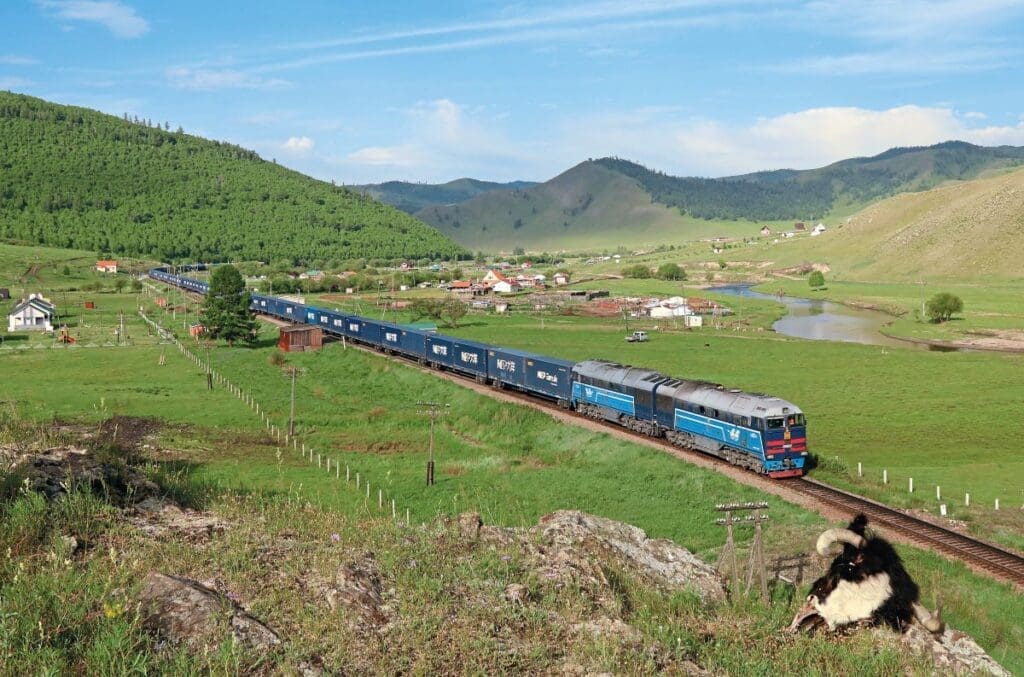

Mongolia’s railway system is focused on freight, and an important source of revenue comes from containerised goods moving between Russia and China – something that has increased in recent years due to the conflict in Ukraine.

In addition, container trains carrying products from China to Europe on the so called ‘New Eurasian Land Bridge’ use the Trans-Mongolian route. Despite the need to go through two bogie exchanges (or changes of rolling stock), this only takes 18 days for the 7500 mile journey compared with the 30-45 days it would take by sea.

There are also imports of oil and gas from Russia, exports of Mongolian coal and iron ore, and internal movement of various commodities – such as coal to power plants and numerous ‘mixed freight’ workings to local facilities at stations and yards along the route.

Passenger services are relatively few and far between. The majority are centred on the capital city UB, with daily return services to the Chinese border at Zamyn Uud, to Sainshand in the Gobi Desert, to the important copper mining town of Erdenet in the north, and twice daily returns to Sukhbaatar on the Russian border. Of particular interest, the UB to Zamyn Uud service (Train 275/276) is one of the most substantial passenger workings in the world, often loading to 27 cars carrying 1200 passengers and totalling over 1800 tonnes.

Other services operate several days a week, with northbound trains that run 450 miles into Russia as far as Irkutsk, and southbound ones to Erenhot on the Chinese side of the border – as well as some that go 300 miles further into China (requiring a bogie change) to the Inner Mongolian capital Hohhot.

Finally, one service operates from Darkhan in the north over the 39 miles to the coal mining town of Sharyn Gol. Previously there were four return services per day, but this is now down to twice weekly, the result of major upgrading of the Darkhan to Sharyn Gol road. Interestingly this is a mixed passenger/freight working.

A weekly international service that took five days to cover the 4900 mile journey between Beijing and Moscow (China Railway train K3/4) via the Trans-Mongolian Railway ceased operation during the Covid pandemic and has yet to restart. Another long-distance service linking Moscow to Erdenet also ended in 2016.

Passenger trains mainly run overnight, with the stock predominantly made up of UBTZ-owned sleeping cars. The majority of vehicles were built during Soviet times and are now in poor condition, with a small number of more modern examples coming from CNR China in 2008. Maximum speed is 100 kph (62 mph) in the majority of locations, although 120 kph (75 mph) is possible on several sections in the Gobi. One of the twice-weekly services to and from Irkutsk utilises Russian Railways (RZhD)-owned stock.

Table 1 provides a summary of UBTZ passenger services.

Table 1: Summary of UBTZ passenger services

| Train No | Departs | From | To | Notes |

| 21 | Mon & Fri | Erlian | UB | Erlian (Chinese/Mongolian border station). |

| 22 | Thu & Sun | UB | Erlian | |

| 33 | Tues & Sat | Hohhot | UB | Hohhot (Inner Mongolia capital). Furthest destination into China. |

| 34 | Mon & Fri | UB | Hohhot | |

| 263 | Daily | UB | Sukhbaatar | Sukhbaatar (Mongolian/ Russian border station). |

| 264 | Daily | Sukhbaatar | UB | |

| 271 | Daily | UB | Sukhbaatar | |

| 272 | Daily | Sukhbaatar | UB | |

| 273/312 | Daily | UB | Erdenet | Via Darkhan. Erdenet is Mongolia’s third city. |

| 311/274 | Daily | Erdenet | UB | |

| 275 | Daily | Zamyn Uud | UB | Zamyn Uud (Mongolian/ Chinese border station). |

| 276 | Daily | UB | Zamyn Uud | |

| 609/285 | Daily | Sainshand | UB | Sainshand (capital of Dornogovi Province Gobi Desert). |

| 286/610 | Daily | UB | Sainshand | |

| 305 | Sat & Sun | UB | Irkutsk | Furthest destination in Russia. Russian & Mongolian stock used. |

| 306 | Tues & Fri | Irkutsk | UB | |

| 601 | Fri & Sun | Sharyn Gol | Darkhan | Mixed passenger/freight service. |

| 602 | Fri & Sun | Darkhan | Sharyn Gol |

Diesels rules

Dieselisation came to Mongolia early with the arrival of three examples of a Soviet copy of an American Alco RSD-1, the TE1, during 1949. This was closely followed by a fleet of 60 TE2s from the Ukrainian Malyshev Factory Kharkiv, delivered between 1950 and 1955 in time for the opening of the line south of UB in 1956. The TE2 was essentially a twin unit version of the TE1, although with a completely different appearance. One of these (No. 418) remains ‘a runner’ as depot mascot in UB, although not in service, while another (No. 522) can be found in the capital city’s railway museum.

The majority of locomotives currently used in Mongolia are of Soviet heritage. At the time of writing, the fleet comprises around 115 main line examples in the power range (per individual unit) 2000-4500hp. Variants of the popular 2TE116 make up over a third of the total fleet and includes four Russian-owned examples on hire to UBTZ that are based at Darkhan for use on local duties.

Increasing numbers of brand new 2TE25KMs continue to be delivered from the Bryansk Works near Moscow, and at the time of writing six examples remain outstanding from the current order. Numbers of earlier designs, such as M62 and twin 2M62, have reduced in recent years, with a handful of single and double units remaining in service, all of which have been upgraded by UBTZ to an ‘MM’ version.

American influence has started to appear with two GE Dash 7s being introduced in the mid-1990s. GE power units have also been retrofitted to several sub classes, with four brand new locomotives based on the GE ‘Evolution’ series also leased to UBTZ.

A few weeks prior to our visit, four examples of an initial batch of 16 Progress Rail SD70ACe/LW units were delivered for use on the ‘Part 1 New Railway Project’ to haul coal trains to China on the Tawan Tolgoi to Gashuun Sukhait route. Finally, Chinese traction in the form of 11 CNR-built CKD4B units entered the scene from 2011 onwards. These are concentrated on branch lines in the Gobi region and the north.

In addition to more powerful main line examples, a fleet of almost 40 1200hp shunting locos – in the shape of TEM2 and more recent TEM18 locos – are distributed across the network. See Table 2 for further information.

Table 2: UBTZ locomotive fleet (June 2024)

| CLASS | BUILDER | PRIME MOVER | FLEET | NOTES |

| TE2 | Malyshev Kharkiv Ukraine. | 2 x Penza D50. | 1 | Still runs. UB depot mascot |

| C30 -7 (Dash 7) | GE Erie. | GE 7FDL. | 2 | 001 in store. 002 on UB depot Scrap Line. |

| M62M-018A/B | Voroshilovgrad/ Luhansk Works Ukraine. | Kolomna 14D40 | 2 | Ex 2M62M-018. Waiting conversion |

| M62UMM (Was M62UM) | Voroshilovgrad/ Luhansk Works Ukraine. | Kolomna 2D49 | 11 | Upgraded by UB depot. |

| 2M62MM (Was 2M62M) | Voroshilovgrad/ Luhansk Works Ukraine. | 2 x Kolomna 2D49 | 8 | |

| 2TE116 | Voroshilovgrad/ Luhansk Works Ukraine. | 2 x Kolomna 5D49 18-9DG | 2 | Numbers 1730/31 |

| 2TE116UM | Voroshilovgrad/ Luhansk Works Ukraine. | 30.5 | 028B written off. | |

| 2TE116UD | Voroshilovgrad/ Luhansk Works Ukraine. | 2 x GE GEVO-12 | 4 | Numbers 074/75/76/77 |

| 2TE116 | Voroshilovgrad/ Luhansk Works Ukraine. | 2 x Kolomna 5D49 | 4 | On hire from RZhD. Used Darkhan area. |

| 2TE25KM | Bryansk Works (BMZ) Russia. | 2 x 16CHN26/26 | 23 | Six more to deliver July 2024 onwards. |

| 2ZAGAL | UB Depot | 2 x GE 7FDL | 8 | Ex M62/2M62/2TE10M rebuilt with GE power units. Two of original ten scrapped. |

| CKD4B | CNR Dalian China. | 16V240ZJD | 11 | Iron ore/coal mining branch lines. |

| TE33AS | JSC Loco Plant Kazakhstan. | GEVO-12 | 4 | |

| SD70ACe/LW-4101 | Progress Rail Illinois. | EMD 16-710G3C | 4 | For ‘Part 1 New Railway Project’. A further 12 on order. |

| TEM2 | Bryansk Works (BMZ) Russia. | Penza PD1 | 24 | Shunting locomotive |

| TEM18 | Penza PD4A | 15 | Shunting locomotive |

The UBTZ fleet is maintained at three main depots: TCh-1 Darkhan in the north, TCh-2 Ulaanbaatar, and TCh-3 in the Gobi at Sainshand. Ulaanbaatar is by far the most comprehensive facility, with the capability to undertake major overhaul and refurbishment, much like a Level 5 depot or locomotive works in Britain. The majority of UBTZ locomotives are also based here.

There are sub-sheds of TCh-1 at Sukhbaatar and Erdenet, and of TCh-3 at Zamyn Uud. Finally, some of the CKD4Bs and the recently-introduced fleet of SD70Aces will be maintained at a new facility located at Gashuun Sukhait on the Tawan Tolgoi Railway.

The main event

For an idea about where to go and what to cover during a visit to Mongolia, I would recommend following the itinerary developed in conjunction with Monrailpic Tours. This covered a large proportion of the Trans-Mongolian Railway by rail, with time spent in and around UB (including the depot there), then south towards China and the Gobi Desert and north towards Russia and Darkhan, taking in several branch lines along the way.

Days one and two were spent travelling from Manchester to Ulaanbaatar via Frankfurt. Then after arriving in UB at 05.20 on day three, it was straight out to our first location linesiding in the Khoolt Pass and Khonkhor area at an elevation of 5,200ft, followed by a UB depot tour. After an overnight stay, on day four we took Train 276 – the 16.40 from UB – overnight to the Gobi Desert.

Day five began at 05.40 by leaving the train at Sumangin Zoo station. This was followed by linesiding at various locations in the Gobi Desert over the next two days, staying overnight in the Ulaan Uul Railway hostel then on to Sainshand. We visited the Zuunbayan branch line before driving back towards UB, with linesiding in the Bayan Pass area en route, where we stayed in a yurt camp for two nights.

On days eight and nine we were south of UB, linesiding in the Bayan/Khoolt Pass and Bumbat station area, then to the Khonkhor/Omega loop and surrounding areas followed by a night in a UB hotel.

Days 10-13 were spent in the Schatan area, driving north from UB to Bayarnbuural and linesiding at the Emeelt Pass, then between Arshaant and Davaany, and near Batsumber en route. Three nights were spent in a Bayarnbuural hotel.

After lunch at the hotel on day 13, we took Train 271 from Schatan north to Darkhan for linesiding in the Darkhan area and two nights in a hotel. Days 14-16 were spent linesiding south of Darkhan, in Tsaidam/ Salkhit area, and the start of Erdenet branch – although the focus of day 15 was the Sharyn Gol branch to photograph the F/ SuO passenger Train 601/602. We then drove south to UB via linesiding north of the Salkhit station area and near to Arshaant, with two nights staying in a hotel.

Day 17 was free UB, so we took in station area views and sightseeing in UB, a farewell dinner, then home on day 18.

I would highly recommend visiting Mongolia, particularly those with a leaning to diesel traction, remote locations, amazing scenery and railway photography in locations where the traction has to work hard. There were some early starts, the accommodation was sometimes less than ideal, and occasionally we had difficulty getting from one place to another (with poor or non-existent roads and an ‘interesting’ standard of driving).

However, none of this rally mattered. We always felt welcome, with a really friendly population and railway staff happy to accommodate our various requests, and we were looked after extremely well by our guide Temuulen, the walking encyclopedia of Mongolian Railways – who is also owed thanks for assistance preparing this article.