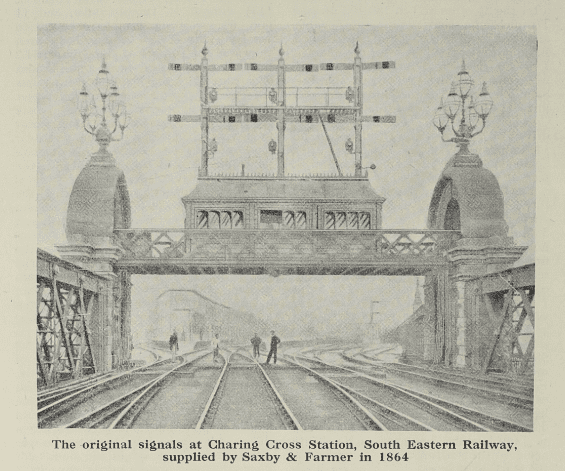

The first signal box at Charing Cross, on the South Eastern Railway (SER), marked a pivotal moment in British railway history. Erected in 1864 by the renowned signalling engineers Saxby & Farmer, it was built specifically for the opening of the new London terminus and remained in use until 1888.

By the time of its installation, Saxby & Farmer were already well established in the railway signalling industry. The Charing Cross box employed equipment manufactured in 1860, utilising what was known as the “rocker” type frame with a grid locking mechanism. This system quickly became popular, not only across Great Britain but also internationally.

Early grouping of railway signals

Incoming and outgoing signals were grouped together, following common practice of the time, and positioned on top of the signal box. Operation was simple and direct, relying on straightforward rod connections rather than more complex mechanical linkages.

From the history of steam through to 21st century rail transport news, we have titles that cater for all rail enthusiasts. Covering diesels, modelling, steam and modern railways, check out our range of magazines and fantastic subscription offers.

Coloured glasses housed within the signal lamps worked on the same principle as the guard’s tri-colour hand lamp. These were rotated using a crank mechanism connected to the familiar up-and-down operating rods.

This signalling arrangement proved effective and remained in use on the SER for many years. In fact, Saxby & Farmer’s agreement with the railway continued for approximately 30 years, later extending to the London, Brighton and South Coast Railway (LBSCR), where the same system was widely adopted.

Visual conventions and evolving practice

One distinctive feature of the semaphore arms was their black vertical stripe on both faces, a visual convention that endured for many years. Later, the SER adopted the practice of painting semaphore arms white, with a red stripe added. Initially, counterweights were not used, as the arms were not counterbalanced. This meant that if an operating rod failed, the signal could fall into a potentially dangerous position.

Mounting signals above the signal box, rather than directly at the fouling points, offered clear advantages. From this elevated position, signalmen had a broad view of the station layout and junctions, eliminating the need for multiple signal runs and complex connections.

Safety limitations of early systems

However, the system also had notable drawbacks. Drivers were required to rely heavily on memory and familiarity with the route, as signals could not always be seen clearly from a distance. In foggy conditions, visibility was especially poor, and a signal indicating “danger” might only become apparent when it was too late to stop safely.

To mitigate this, signalmen often grouped multiple signal arms on a single post, providing additional visual cues. At Charing Cross, four extra arms were later installed above the central set, significantly increasing the height of the signal post and improving visibility.

From visual telegraph to modern signalling

The entire signalling system was derived from the principles of the visual telegraph, with its primary function being the transmission of instructions rather than the enforcement of absolute stops. Trains did not necessarily halt at the point where a signal stood; instead, drivers interpreted signals based on their understanding of the station or junction ahead.

A comparable example could be seen at the Cannon Street terminus, which also employed four signal arms above its carriage sheds. By 1926, the reading of all signals had been formalised, meaning that signal interpretation no longer relied solely on driver familiarity — a major step towards modern railway safety.

Even so, in poor visibility, particularly fog, the lights mounted at the tops of tall signal posts remained difficult to see, even from relatively short distances. These limitations ultimately drove the development of improved signalling technologies and stricter operating rules in the decades that followed.

The original article appeared in a 1949 edition of The Railway Magazine. Subscribe and access our FULL archive of editions going back to 1897! https://www.classicmagazines.co.uk/the-railway-magazine