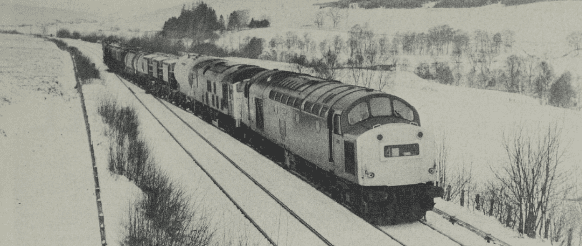

From the January 1977 archive, this first-hand account follows a winter rail journey over the Highland Main Line, travelling on the “Royal Highlander” and “Clansman” amid snow, summit climbs and Class 40 and Class 47 haulage.

Living in Southern England and planning the trip

LIVING in a sheltered part of Southern England where snow is extremely rare, we become excited when we get a little—and a little is all we normally do get, only a few flakes. Even when there are reports of severe conditions over most of the country, we are usually clear. Wind, gales and severe frost, yes, we get those in plenty, but not much snow. My wife and I love a challenge and, although I never achieved my ambition of getting a good snow shot in steam days, she still seemed hope of obtaining a good one, so with this in mind winter’s leave was rostered for February 1-5 so we decided to go to the Far North for a change, instead of our old haunt at Shap.

As is usual with us, all was well arranged weeks ahead of departure time: sleepers and car-hire booked; train services worked out; and even a plan as to where we could see the few trains that run on the Perth–Inverness, Glasgow–Fort William, and Inverness–Kyle lines. The only thing we couldn’t arrange was the weather.

From the history of steam through to 21st century rail transport news, we have titles that cater for all rail enthusiasts. Covering diesels, modelling, steam and modern railways, check out our range of magazines and fantastic subscription offers.

A friend offered the chance to borrow a telephoto lens on a 35-mm. camera. Now, being a traditionalist, I do not normally use this medium, being a large-format standard-lens photographer. But why not? So we gladly accepted. All was set. We were to travel north on the “Royal Highlander” on the Saturday evening so I worked that morning, full of excitement as it were on. For once, time in the signalbox seemed to drag, but at length 14.00 arrived and I was off, home to a meal and then away for that well-earned break. Was it to be a break? Not really, I suppose, but more a busman’s (or should I say railwayman’s) holiday. However, we are like that: trains are my life and my wife’s too. Scotland here we come.

Photo: D. E. Canning

Departure and breakfast on the “Royal Highlander”

Most trips of this nature have their ups and downs, and this one proved to be no exception. As we packed all our equipment in the car, snowflakes began to fall. The weather had in fact been bitter cold for days beforehand, but dry. “Hug,” said my wife, “going all up there for snow and I suppose we are going to get it here now.” “Never mind, it’s different there. You will never see snow here like it can be at Druim-uachdar,” said I, to cheer her up. Into the car and off—but dead, it refused to go. After some persuasion, however, we were on our way and just managed to get to Theale in time to catch the 18.05 Bedwyn–Reading.

I had worked out this would connect with the 15.55 Paignton at Reading for Paddington, if all was well, and it certainly was. Within ten minutes we were enjoying the first of the “ups” of the trip. The Paignton ran into Reading packed solid, except for the first class, but I was certain I saw some white labels on the leading coach. We scrambled to the front and, sure enough, a completely empty e.t.h. first-class open had “for use of second-class passengers” on it. We rode into London, the coach to ourselves, feeling like royalty; we even had a photographic session en route without bothering anyone.

All too soon, 29 min. later, it was over and we were in Paddington, and struggling with our cases onto the Underground and by foot to arrive at Euston in time to have a meal, after which we planned to try some night shots of our train, the “Royal Highlander,” before departure. I thought we might experience trouble here, getting onto the platform early, but no, and believe it or not we were even helped by one member of staff who put his route number straight for us.

Soon it was time to board the train. The sleeping-car attendant came round to collect our tickets and we asked for “Two breakfast trays in the morning, please.” Imagine my horror when he said “No breakfast trays on this train, sir.”

“What?” It definitely stated in the leaflet sent with our tickets, “Breakfast trays available, order from steward on train.” As there is no buffet or restaurant on the Scot train, which does not get to Inverness till 10.30—thirteen hours with no food or drink—it was a last-minute dash out to the buffet on the concourse to stock-up. And yes, needless to say, with less than five minutes to departure time, a queue ten deep. Somehow or other I panted out my plight and got served first, and jumped into the last coach just in the nick of time. This, I suppose, was quite comical seeing we had been on the platform an hour before departure. I really could have given the porter who remarked that I should get up earlier to sleep one if my mind—if I had had time!

Photo: D. E. Canning

Overnight journey and arrival in Inverness

We settled down to sleep, and the first thing I remember is coming-to, as we stopped with a sudden jerk. Curiosity got the better of me so I peeped out of the window. It was 02.30. “Penrith,” declared the station name, so I got back to bed. I did not sleep much again, but did not look out until I estimated we were at Perth, but the sign then read “Gleneagles”—one out! After Perth I woke my wife, who snored blind she did not sleep a wink all night, despite the fact she kept me awake after Penrith snoring. There was no snow at Perth but praise be, it was a clear frosty morning.

As we climbed past Blair Atholl the sun came up and the mountains appeared on each side, covered with what looked like icing sugar.

Then, as we got higher, patches of snow appeared nearer the line. Suddenly, near Dalnaspidal as No. 47 550 roared away at the head of the 14 coaches at a speed not exceeding 20 m.p.h., the scene changed dramatically. As we topped Druimuachdar Summit, it seemed a different world: snow on the mountains, the lineside, on the trees, in fact everywhere. The sun was shining, making the mountain tops look as though they were on fire, and deer were down close to the line, rummaging in the snow for food.

This was too good to be true. I must be dreaming. A knock at the door proved me not to be. A cup of tea had arrived, so we had this with our buffet breakfast as the train rolled downhill towards Aviemore. There was no snow there, but some again at Slochd. We arrived at Inverness at 11.00 and, as we lugged our cases up the platform, the sun shone warm on to us. There was no wind and, unlike when we left home in Berkshire the previous afternoon, it seemed like a summer’s day.

Photo: D. E. Canning

“Clansman” and photography in the Highlands

There was only one other train over the line on Sundays in daylight, so as soon as we had reserved seats for the return journey on the “Clansman” on Thursday we found our hire car and were on the road back to Slochd to see the 08.45 Edinburgh–Inverness. On arrival we experienced a new problem: where to set up to take the photographs as all the laybys were full of snow. In this case we pulled into a side road, and walked to the spot we decided on. “Horror of horrors”—the sun was beautiful, but the cutting was in shadow, a problem we came across many more times during the stay. The exposure for the sun on snow was 1/1000-f.16. And off the shadows side of the bridge 1/1000-f.4. Ah well, put exposure meter away in bag and hope experience, choosing 1/1000-f.5.6 on range finder. At length we heard the approaching, but got quite a surprise when a class “40” appeared. We were expecting a “26” for some reason. Anyhow, I took it, and how nice it looked too. What the result would be only time would tell. And that was that: for Sunday. The service over the line is sparse—only six in daylight even on weekdays during the winter—so once more we carefully had be up early. But the best of plans can go wrong!

Two trains in the early morning were due to cross at Carr Bridge, the place where we were staying, so after a lot of negotiation with our host we managed to get breakfast on the second morning at seven and we were off at eight to Slochd, where we photographed the up one, although the light was bad in the cutting. We then made for the place I had in mind for the down one, and set-up just as it could be heard slogging up the hill. As it came into view the cloud broke and out came the low morning sun, straight into the camera lens: nice to see the sun, but not in that position! I tried to make a quick move at the last minute, but disappeared to my waist in a hole full of snow, much to the amusement of my wife and the locomotive crew, so I did not get that one. It was then 2½ hours till the next train, so we proceeded on towards the summit, at Druimuachdar, but low cloud covered the mountains that day, so we got what we could at Dalnaspidal.

Next day things were different. We woke up to glorious sun; hoar frost clung to the trees and bushes; the lakes were like mirrors; and the roads like ski runs, so we gingerly made our way to Dalwhinnie and the summit. It was unbelievable. There was not a cloud in the sky; the mountains towered up into the blue; but—and there often is a but—the sun was on the wrong side. Still, can’t complain for it’s fine and clear. We will have to get over the summit, to the other side. This proved to be somewhat harder than we expected, with snow lying 18 in. deep and with innumerable deep holes filled and hidden by the snow, but at length we made it, and it was then we realised it had been worth lugging Wellington and sunglasses all the way up with us. Here also I thought was a chance to try the 135-mm. lens, as yet not used on the trip. Time passed and after about half an hour, we were in the snow up to our knees, began to wonder if we were mad, but then at least no one else would have the pictures we were hoping to get.

At length the “Clansman” passed and it was recorded on film. There were some queer looks from passengers but a friendly wave and toot from the driver, who I think recognised us from previous days. We took the train which left the “Clansman” at Dalnaspidal, from the same spot albeit almost straight in the sun. By now we were frozen to the bone and it was two hours to tea, so we plodded back to the car and got out the stove to make tea. In the process thereof we realised a train was coming, and as a short freight train came in the scene again the 135-mm. lens came into its own. The other trains of the day were all photographed in sunny positions as we could get to the snow, although being very scenic, made it awkward to get to where we really wanted. We were content as we drove back to Carr Bridge that night. On the Monday we had learnt our lesson, trying to do too much, by attempting to drive to the Fort William area to get a shot on that line, then to come back and get another on the Perth–Inverness line—and finished missing them both. We never did get to the Kyle line either!

Photo: D. E. Canning

Return journey and final reflections

As we arrived at Inverness so we left, for the sun was brilliant as we boarded the “Clansman.” Sharp at 10.30 we were away as 47 550 (again) roared up the bank to Culloden Moor. I felt satisfied with our stay and I know my wife felt likewise. We were both surprised at the number of class “47’s” working over the line, also the variety on summer numbers of trains, for we also noted “40’s,” “24’s” and “26’s.” I believed we had seen the line at its best, albeit only for a short while. As we gained height we were into the snow again, like going into another world, on past Slochd, Carr Bridge, Aviemore, Kingussie, Newtonmore, where for the past four days we had driven and walked more than 200 miles in the snow.

Approaching Dalwhinnie I realised just how lucky we had been the day before. The sky grew dark and the sun disappeared; thick cloud came down over the mountains and sheets of sleet beat across where we had stood in photographing that train 24 hours earlier, in brilliant sunshine. And that was the end of the sun, the rest of the journey being in cloud, mist and rain. As we descended rapidly, the snow soon disappeared, only to remain a memory of a winterbreak that to me really was, for a change, a break to remember.

This article is available to subscribers of The Railway Magazine, along with every article from issues dating back to the 1800s! To subscribe, visit https://www.classicmagazines.co.uk/the-railway-magazine