By CYNRIC MYTTON-DAVIES

Introduction and Closure Announcement

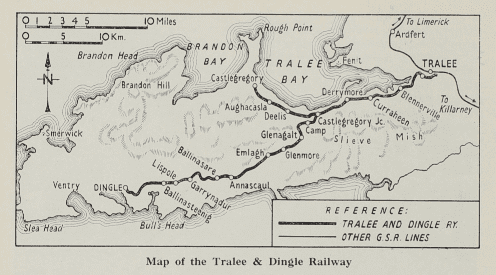

ONE of the most westerly lines in Europe will no longer be available for passengers by the time that this issue of THE RAILWAY MAGAZINE appears, for the announcement was made on March 15 that the Tralee & Dingle Light Railway is to be closed to passenger traffic on April 17. The main line from Tralee to Dingle will continue to convey goods traffic, but the branch line from the junction to Castlegregory is being closed entirely. The Dingle peninsula, which this railway serves, is the northernmost of the four arms of land that stretch out into the Atlantic from the south west corner of Ireland. The line had its origin in the Tralee & Dingle Light Railway Co., Ltd., which was incorporated on June 4, 1884, under the Tramways & Public Companies (Ireland) Act, 1883. Under the original powers and those granted by the Tralee & Dingle Light Railway Order of 1888, some 37⅔ miles of 3 ft. gauge single track were built, and opened on March 31, 1891. Baronial guarantees were given to enable the capital to be raised, and, owing to continual deficits in working, the line was transferred in 1896 to the Grand Jury of the County of Kerry and thereafter controlled by a Committee of Management. In 1925, at the time of grouping in Eire, the Tralee & Dingle Railway merged into the Great Southern Railways, but up to that time it had its own works and repair shops at Tralee, the headquarters of the undertaking. Since then locomotive repairs have been effected at the company’s works at Inchicore instead of in the shops at Tralee, and carriage and wagon repairs undertaken at Limerick.

Naturally this narrow-gauge railway has its own station at Tralee, which stands some few hundred yards distant from the (Irish) standard gauge station; the track, however, actually runs on through the streets right into the sidings of the main station in order to facilitate the transfer of merchandise and parcels from the narrow to the standard gauge vans and wagons and vice versa, but passengers are not carried on to the main station. When the Tralee & Dingle Railway was described in THE RAILWAY MAGAZINE for May, 1898, in an article by Mr. T. J. Goodlake, there were two standard-gauge stations in Tralee, as both the Great Southern & Western Railway and the Waterford, Limerick & Western Railway had separate termini at Tralee adjoining each other and connected end to end. After the amalgamation of the W.L. & W.R. and the G.S. & W.R. in 1901, however, the W.L. & W.R. station was closed and all standard-gauge trains transferred to the G.S. & W.R. station.

From the history of steam through to 21st century rail transport news, we have titles that cater for all rail enthusiasts. Covering diesels, modelling, steam and modern railways, check out our range of magazines and fantastic subscription offers.

Castlegregory–Tralee through coach is being backed on to a Dingle–Tralee train by the locomotive in the foreground

Photo: W. A. Camwell

Route and Operation

The configuration of the Dingle peninsula is roughly that of a long mountainous backbone, which rises to a crest at about one-third of the way westward and roughly half way along the main line, so that from Tralee to Dingle the trains are climbing all the time for the first half of the journey and then descending for the remainder of the way, although there are, of course, inclines and declivities on both sides of the crest. This crest is the culminating point of a 3⅓ mile bank between Castlegregory Junction and Glenagalt, which has a gradient of 1 in 30; the highest point is reached at Glenagalt, 680 ft. above sea level. The track is of the flat-bottom type, and single line working obtains throughout, but there are passing loops and sidings at Castlegregory Junction and Annascaul. Since, however, there are now only two trains daily in each direction, the loops are not normally required.

There are seven locomotives, numbered 1 to 6 and 8, in service on the line at the present time. They are all English built, six having been constructed by the Hunslet Engine Company’s works at Leeds, and one by Kerr, Stuart & Co. Ltd. The first three engines were 2-6-0 tanks, with outside cylinders (13 in. × 18 in.), built by Hunslet in 1889. Nos. 1 and 2 were rebuilt in 1903, and No. 2 in 1902. No. 4, a Hunslet product of 1890—a much smaller locomotive—was an 0-4-2 intended for the Castlegregory branch. In 1892 the Hunslet Engine Co. supplied No. 5, a somewhat larger tank engine of the 2-6-2 type, but with No. 6, supplied by the same maker in 1898, the railway reverted to the familiar 2-6-0. Kerr, Stuart & Co. Ltd., supplied Nos. 7 and 8 in 1902 and 1903 respectively, and these also were of the 2-6-0 with outside cylinders. In 1908 No. 4 was scrapped, and the Kerr Stuart No. 8 was renumbered as 4. The other Kerr, Stuart engine was scrapped in 1928, leaving the number 7 vacant. The railway reverted to the Hunslet Engine Company for its last order, which was placed in 1910, and was for the present No. 8, a 2-6-0 tank generally similar to the original three.

All the locomotives are fitted with cowcatchers, since the track runs for the most part along the side of the main road, where cattle and sheep frequently wander at large. In many places there is no dividing wall or fence between the road and the rails, and level crossings are frequent, and sometimes unprotected. Each locomotive is also fitted with a large and powerful acetylene headlamp at the base of the chimney.

Rolling Stock and Stations

All cars and freight wagons are built with bogies, passenger cars are eight-wheeled and straight sided, and the finish gives a match-boarding effect; the doors open inwards. The interiors are divided into two compartments, one of which is about twice the length of the other. In the long section the seats run along the sides of the car, and in the small one across the car. The third class coaches have wooden, and first class upholstered seats of the same design as is standard for first class rolling stock throughout the Great Southern system. All windows in both classes are fitted with two bars, so that it is impossible to lean outside.

There are thirteen stops, most of which are optional, between the main line terminals, and six between Tralee and Castlegregory. Most of these are “flag” stops, having neither platforms nor buildings, and are marked only by a gate and a nameboard inscribed in both English and Irish characters. Only Lispole, Annascaul, Camp, and Castlegregory Junction have platforms, and these are also the only stations at which there are booked stops. At Camp and at Annascaul locomotives take in water, as it is between these two points that the steepest section of the line is situated.

Opposition and Survival

It was only to be expected that there should have been a certain amount of opposition to the inception of the line, on the part of the inhabitants of the Dingle peninsula, who felt that their happy, self-contained little world was being invaded and linked up with the great world of commerce, stress and trouble, that its peculiar characteristics would soon be lost, and that it would become spoiled. Some of these people resorted to active measures against the railway, and local railway officials have some amusing stories to tell of the attempts that were made to discourage the service, including that of one Paddy Kennedy who, on one occasion, resorted to soaping the rails! This, however, did not achieve the result that Paddy had hoped for, and the railway remained.

It is interesting to compare that original hostility with the present-day affection for the line that is held by most of the people. In spite of the journey time for the thirty-two odd miles being two and a half hours, a bus service which covered the distance in a much shorter time, and which was inaugurated a few years ago, had to be discontinued owing to lack of support, the people preferring the railway. There are some who assert that the line has been kept open only for the entertainment of visitors, and would themselves welcome its substitution by a regular service of Great Southern buses, but the fact is that it handles a really considerable freight traffic. Although buses are now to serve the passenger needs, the main line to Dingle is to continue in use for goods. For purposes of a lower standard of maintenance is, of course, contemplated.

On the non-technical side it may be said that this railway traverses some extremely beautiful country, and the views from the carriage windows are among the best in Eire. Mountain ranges, surprising glimpses of the sea penetrate inland in charming bays, deep valleys, wild heath and bogland, and little green fields on the plains are all to be seen as the train takes its leisurely way down the peninsula. The terminus of the line at the western end is Dingle station, but the rails continue further, down to the port, and freight wagons are regularly taken to the little goods platform near the pier to be loaded with fish and the merchandise—much of which is coal brought in by the small steamers that call from Cardiff, Swansea, and other Welsh and West England ports.

Timetable and Services

The general direction of the main line is from north-east to south-west. It follows the southern coast of Tralee Bay, which is the northern coast of the Dingle promontory, from Tralee to Castlegregory Junction, whence the branch line continues along the coast, then it strikes inland through the Glen na Gault and reaches the southern coast near the Inch. Peninsular, slightly east of Annascaul, after which it follows westward for the remainder of the distance, keeping a mile or so inland, behind the foothills of the mountains which are known as the Slieve Mish. Beyond Dingle there is no transport system whatever, so that the scene before the departure of the trains to Tralee is fascinating and interesting, with carts, pony traps, jaunting cars, and a few motors all drawn up in the diminutive station yard, unloading parcels, luggage, and passengers. The same is true of Tralee, particularly on Saturdays, when the local market day, when every shop in the town seems to deliver customers’ purchases to the train.

The composition of the trains is usually locomotive, goods wagons, composite first and third class coach, third class brake coach, and then another third class coach, all bound for Dingle. These are followed by another set of cars for Castlegregory, and goods wagons for the same destination on the extreme rear. A spare locomotive with steam up is in readiness in a siding at Castlegregory, by the time the train arrives, to haul the rear portion of the train for its last six miles. Running time is allowed as follows: Tralee to Castlegregory Junction 10 miles with three optional halts, 40 minutes; Castlegregory Junction to Castlegregory, 6 miles with two optional stops, 36 minutes; Castlegregory Junction to Annascaul, 11½ miles with four optional stops and 3¾ mile bank with 1 in 30 gradient, 65 minutes; Annascaul to Lispole, 6 miles with two optional stops, 25 minutes; Lispole to Dingle, 5 miles with one optional stop, 20 minutes. This timing applies both to the morning and afternoon departures from Tralee. In the reverse direction the schedule varies a little.

Photo: W. A. Camwell

The 7.30 a.m. train from Tralee serves the main line only, the 11.55 serves the Castlegregory line only, maintaining the previously specified schedule, and the 5.30 p.m. serves both main and branch lines. In the up direction, there is a train from Castlegregory to Tralee at 8.10 a.m. from Monday to Friday and 9.50 a.m. on Saturday, still keeping the same schedule, and another every weekday at 3.55 p.m. which connects with the afternoon train from Dingle. The morning train from Dingle makes no connection at the junction from Castlegregory. There are no trains in either direction on Sundays.

This original article can be accessed in The Railway Magazine archive, along with all issues dating back to the 1800s! All you need to do is be a Railway Magazine subscriber: https://www.classicmagazines.co.uk/the-railway-magazine