There has long been a peculiar and enduring interest in new locomotive designs emerging from Swindon. For decades, the works of the Great Western Railway have set benchmarks for locomotive engineering in Britain, and it has become increasingly clear how deeply engineers across the industry have been influenced by Swindon practice.

By the mid-1940s, it was widely understood that the first example of a new class of locomotive for the GWR, designed under F. W. Hawksworth, Chief Mechanical Engineer, was under construction. From the outset, it was known that the design would incorporate a number of significant new features. Both in the drawing office and the erecting shops, the utmost secrecy was observed, leading to widespread rumour and speculation about the nature of the new engine.

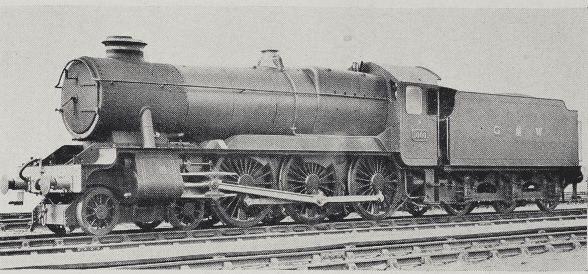

When details were finally released, it became evident that the well-established “Modified Hall” class, notably No. 6959, had formed the starting point for the new design. The first completed engine, No. 1000, demonstrated that while the design was not revolutionary in the absolute sense imagined by some observers, it nonetheless represented a noteworthy departure from long-established Swindon practice dating back to the era of George Jackson Churchward. Many of the refinements trialled on the Modified Halls were brought together in this new locomotive, marking the first major modification to the long-established “Swindon No. 1” boiler for many years.

From the history of steam through to 21st century rail transport news, we have titles that cater for all rail enthusiasts. Covering diesels, modelling, steam and modern railways, check out our range of magazines and fantastic subscription offers.

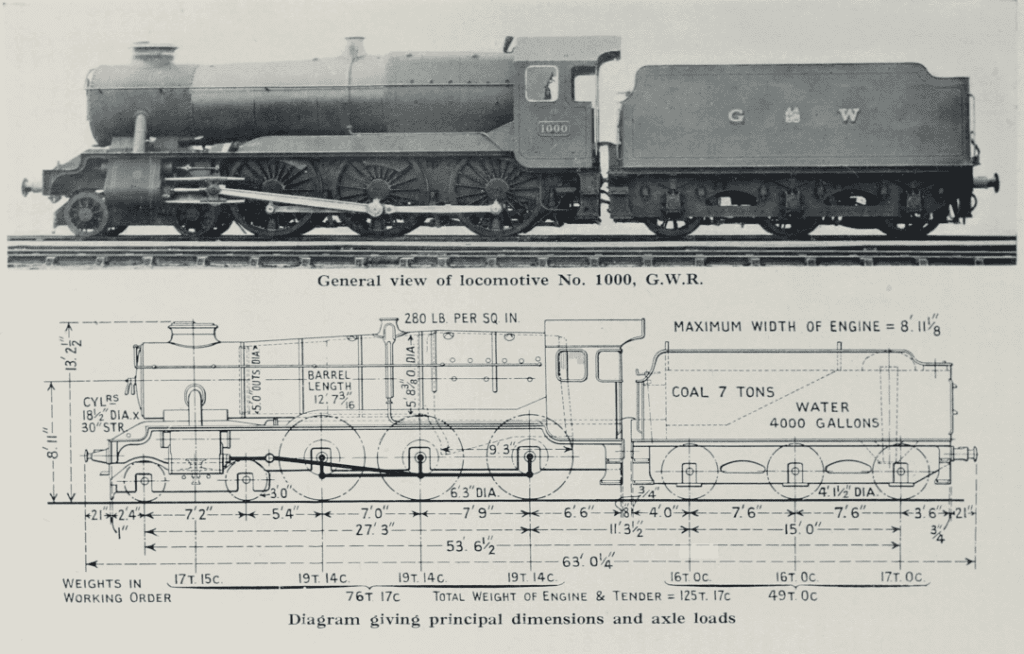

The boiler was the focus of the most extensive changes. The most striking feature was the increase in working pressure to 280 lb per square inch, establishing a new record for the Great Western Railway. This placed No. 1000 alongside the Southern Railway’s Merchant Navy class as the most highly pressed locomotives operating in the country.

While the number of superheater flues remained at 21, as on the Modified Hall class, the superheating surface was reduced from 314.6 sq ft on No. 6959 to 265 sq ft on No. 1000. The evaporative surface showed only a minor reduction, from 1,737.5 sq ft to 1,714 sq ft, but this was achieved through a significant change in tube arrangement. The number of small tubes increased from 145 to 198, while their diameter was reduced from 2 inches to 1¾ inches. The firebox heating surface was also increased by approximately 14 sq ft, and it was stated that the revised superheater arrangement produced a higher degree of superheat than earlier designs.

A further point of interest was the introduction of a double blast pipe and chimney, fitted to the first engine of the class for experimental purposes. In addition, a hopper-type ashpan was adopted to allow more rapid removal of ash at depots, improving operational efficiency.

The main frames were constructed entirely of steel plate, with the cylinders cast separately. A fabricated steel saddle plate was fitted between the front ends of the frames to support the smokebox and the front end of the boiler. The overall appearance of the locomotive’s front end closely resembled that of the Modified Hall class, particularly in the downward slope of the framing from the smokebox to the buffer beam.

A plate-frame bogie was retained, featuring a fabricated centre and independent springing. The coupled driving wheels measured 6 ft 3 in in diameter, maintaining the proportions familiar to Great Western express locomotives.

The tender represented a more radical departure from traditional Swindon practice than the engine itself. Designed as a simpler form of construction, it was built entirely by welding rather than riveting. It carried 7 tons of coal and 4,000 gallons of water, and achieved a notably favourable ratio between empty and loaded weights — 22 tons 14 cwt empty, compared with 49 tons loaded.

In overall appearance and finish, No. 1000 was widely regarded as an attractive locomotive. A continuous splasher marked a visible difference from the Hall class, while the double chimney was considered particularly well proportioned. Although the absence of a locomotive name was regarded by some enthusiasts as regrettable, this was offset to an extent by the prominent and well-executed Great Western coat of arms carried on the tender.

The principal dimensions of Locomotive No. 1000 were as follows:

- Cylinders: Two, 18½ in diameter

- Stroke: 30 in

- Piston valves: 10 in diameter

- Coupled wheels: 6 ft 3 in diameter

- Coupled wheelbase: 14 ft 9 in

- Total wheelbase (engine): 27 ft 3 in

- Total length (engine and tender): 53 ft 6½ in

Boiler:

- Maximum outside diameter: 5 ft 8½ in

- Minimum diameter: 5 ft 0 in

- Barrel length: 12 ft 7¾ in

- Working pressure: 280 lb per sq in

Heating surfaces:

- Fire tubes: 1,545 sq ft

- Firebox: 169 sq ft

- Total evaporative surface: 1,714 sq ft

- Superheater surface: 265 sq ft

- Total combined heating surface: 1,979 sq ft

Weights in working order:

- Engine: 76 tons 17 cwt

- Tender: 49 tons

- Combined: 125 tons 17 cwt

Tractive effort:

- 32,580 lb at 85 per cent boiler pressure

Taken as a whole, Locomotive No. 1000 represented a careful and considered evolution of Great Western practice rather than a radical break from it. The locomotive demonstrated how Swindon engineers were able to refine long-established principles to meet modern demands, and many observers believed that its innovations would influence other classes in the years to come.

For today’s reader, this locomotive stands as a fascinating example of post-war British steam engineering at its most refined — progressive without abandoning tradition, and firmly rooted in the engineering philosophy that made Swindon famous.

This has been extracted from the Nov/Dec 1945 issue of The Railway Magazine. All subscribers to The Railway Magazine can access the full, searchable archive! https://www.classicmagazines.co.uk/the-railway-magazine