In January 1960, Britain’s railways were once again battling one of their greatest recurring enemies: severe winter weather. An article published in The Railway Magazine that month, written by M. Harbottle, District Engineer (Inverness), Scottish Region, provides a detailed insight into how British Railways planned for, responded to, and survived heavy snowfall in some of the most exposed parts of the network.

The Highland challenge

The Highland District of the Scottish Region presented some of the most extreme operating conditions in the country. Stretching from Blair Atholl to Wick, a distance of 244 miles, the route included long single-track sections, high-altitude summits such as Drumochter (1,484 ft), Slochd (1,315 ft) and Dava Summit (1,052 ft), and vast areas where drifting snow could completely block the line.

Snow in the Highlands was categorised into two main types:

From the history of steam through to 21st century rail transport news, we have titles that cater for all rail enthusiasts. Covering diesels, modelling, steam and modern railways, check out our range of magazines and fantastic subscription offers.

- Light, powdery snow, which, when combined with high winds, caused severe drifting.

- Large flakes of “wet” snow, which did not drift but created dense cover that made ploughing difficult and impaired locomotive performance.

Snow ploughs and early intervention

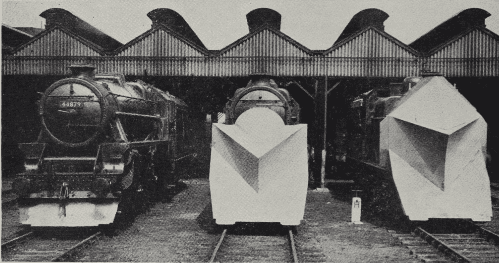

British Railways relied heavily on snow ploughs, ranging from light designs for clearing shallow snow to heavy-duty ploughs capable of forcing through deep drifts. However, ploughing “wet” snow significantly reduced locomotive performance, making early intervention essential.

The article stresses that snow ploughs were not barriers, but tools designed to prevent accumulation. Correct siting of snow fences and plough deployment was critical to avoid creating worse conditions through turbulence and redeposition.

Snow fencing and wind management

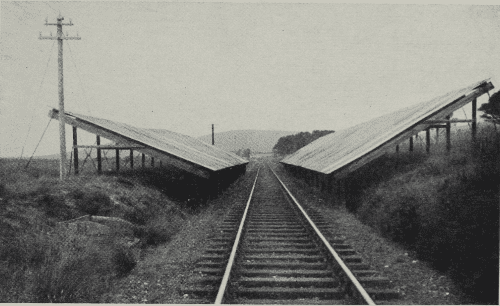

One of the most important long-term defences against drifting snow was the strategic use of snow fences, positioned 60–90 feet back from the cutting edge to prevent wind eddies forming over the track.

Early timber fencing was later refined into lean-to structures, designed using principles similar to the Venturi effect, increasing wind speed over the track to carry snow away rather than allowing it to settle. These structures were particularly effective in exposed areas but were costly to construct, limiting widespread use.

Switches, crossings and signalling

Snow presented particular problems at points, switches and crossings, where packing could cause failures. Mechanical heating using oil, gas or electricity was impractical in remote Highland locations, so manual clearance and the application of paraffin vapour flame guns were often used instead.

Snow accumulation also affected signalling systems, requiring close coordination between engineering staff, signal engineers and operating departments.

Operational response and organisation

The article details a highly structured response system. When conditions deteriorated:

- Engineering and operating officers conferred immediately.

- Heavy snow ploughs were deployed.

- Freight loads were reduced or services cancelled if necessary.

- Special meteorological reports from the Meteorological Office guided decisions.

If blockages occurred, length gangs were mobilised, supported by emergency trains carrying tools, food, blankets and hot drinks. In extreme cases, relief engines were attached in rear to assist stalled trains.

Snowbound trains and rescue procedures

Snowbound passenger trains were given priority. If necessary, passengers were rescued and taken to the nearest station, while the blockage was tackled from both ends using ploughs and hand-cutting methods.

Clearing procedures included:

- Cutting trenches across the track to relieve compression

- Attacking drifts from both directions

- Gradual removal of rolling stock to reduce obstruction

Lessons learned

The article concludes that effective snow clearance depended on forward planning, cooperation between departments, and experienced railwaymen, rather than brute force alone. It acknowledges that while machinery and engineering solutions were vital, success ultimately relied on human judgement, endurance and teamwork.

The winter of 1959–60 would go down as one of the most challenging periods for British Railways — and a testament to the ingenuity and resilience of those tasked with keeping trains moving against the odds.

The original article appeared in The Railway Magazine